Forty years ago on 3 August 1975 I was charged under the Terrorism Act after 6 weeks of detention during which I was tortured. This is the account, from my book Inside Apartheid’s Prison, of my trial, in three parts.

CHAPTER 6

Awaiting trial

I HAD never seen a door as massive and heavy as the steel one that shut behind me in Durban Central Prison. It shocked me in a way that the loudly crashing doors in detention had failed to do. There was something very final about the way it closed.

This door was at once a physical barrier to movement and symbolic of a change in my life. My previous life was now excluded, part of the “outside.” In the years that lay ahead, my life now belonged to the “inside.”

Normally, we close doors to provide personal security, comfort and safety. Behind the door of one’s home there is usually warmth, harmony and contentment. A prison door, in contrast, locks you into a world that strips you of your dignity. Here, comfort is absent and there is no personal privacy. There is also a constant barrage of unwelcome sounds.

Although I did return through this door in 1975, it was only to be taken to court or another prison. My next opportunity to open a door for myself, away from prison sights and sounds, was not until my release in 1983.

At the same time as I was shut out from one life, I was, in a sense, publicly connected to another, that of the liberation movement. What was lacking in my period underground, when I had to hide my beliefs and connections, was now publicly known and asserted.

I felt relieved about this, and a sense of pride in being seen for what I truly was. The courts might rule that I had acted disgracefully, but I could now declare myself — and be seen to be by those who shared my beliefs — a part of the struggle to provide a better life for all South Africans.

The prison door had shut me out of the privileged life of a white South African. For the first time, I experienced some of the discomforts that are the normal lot of the black majority. I was now shut out from privilege, and from my relatively esteemed position as a professional and university lecturer. My identity was now that of a prisoner, removed from society.

There were, I knew, people who held me in high esteem as a freedom fighter. But they were far removed from the interpersonal relations that I experienced behind prison walls. The prison authorities saw me as a person who threatened the state and had to be held in secure prison conditions, away from other prisoners who might be influenced by my “terrorist perspective.”

Being in prison does not come naturally to anyone. The concrete floors and walls and steel surroundings are alienating, and a cell is quite unlike the home of any person, rich or poor. Although one is “inside” one always feels like an “outsider.”

That is why, at first, I experienced prison life as if I were an outsider looking in. On one level, I accepted that I was a political prisoner. In fact, I was proud of it. But part of me could never accept the “prisoner” tag, or having been thrown in jail because of what I stood for.

I had thought a lot about the political context of what I had done. I knew I was one of many people imprisoned for their beliefs. But I had now to deal with the reality of spending years inside. And I had not really understood what that would mean.

How does one describe the physical conditions of a prison? Much has been written about them, their peculiar atmosphere, and the impact they have on inmates. One thing I have been trying to understand is the symbolism, and psychological legacy, of their constrained spaces. I have thought a lot about what prison meant to me and continues to mean in my life.

My experience of prison is still with me, more than 10 years after I was finally released. It is something that makes me want to get out of claustrophobic, overheated rooms, to have access to fresh air and light, to avoid dark and dingy rooms and have a sense of space. It also resurfaces when I am forced to be with people with whom I have little in common.

What I found most oppressive was the absolute denial of everything I really wanted to do. This not only involved being confined to a physical space, but the imposition of sights and sounds that were unwanted and unwelcome.

Just as in the police cell, there was no raised bed in the prison cell. I slept under blankets, on a mat placed on the cement floor. But the cell did have a basin and was clean. I was also permitted, under South African law, to have reading matter, and soon collected a lot of literature.

Obviously, the prison authorities had never encountered anything like this before, for they had no bookcases or were very reluctant to supply anything to house more than a Bible. I was supplied with very makeshift containers to accommodate my books.

I was the only political prisoner in the prison. Most of the other prisoners were awaiting trial. As remains the case today, many of these people waited months in jail before their cases were settled.

The prison was all grey and steel. These two words define the textures, the materials and colours I would have to deal with for a long time. In prison, there is little you want to touch or look at. The mat was rough, the blankets uninviting. There was nothing comforting or homely about what was to be my home. There was no garden and there was little time to see the sky. I was allowed out into a small part of a yard for half an hour in the morning and half an hour in the afternoon. If I had a visit, it substituted for exercise. The rest of the time I stayed in my cell. And I could see nothing outside of it.

The prison officials, however, treated me satisfactorily. Only one of them had had any previous contact with political prisoners. He had briefly guarded Rivonia trialist Denis Goldberg, who, he said, was in for “sabotation” (an adaptation of the Afrikaans word for sabotage).

In fact, at this time Denis Goldberg was serving a life sentence in Pretoria, where I would later join him.

I was charged under the Terrorism Act on August 3, 1975. But this was merely a formality. The actual trial would start two months later.

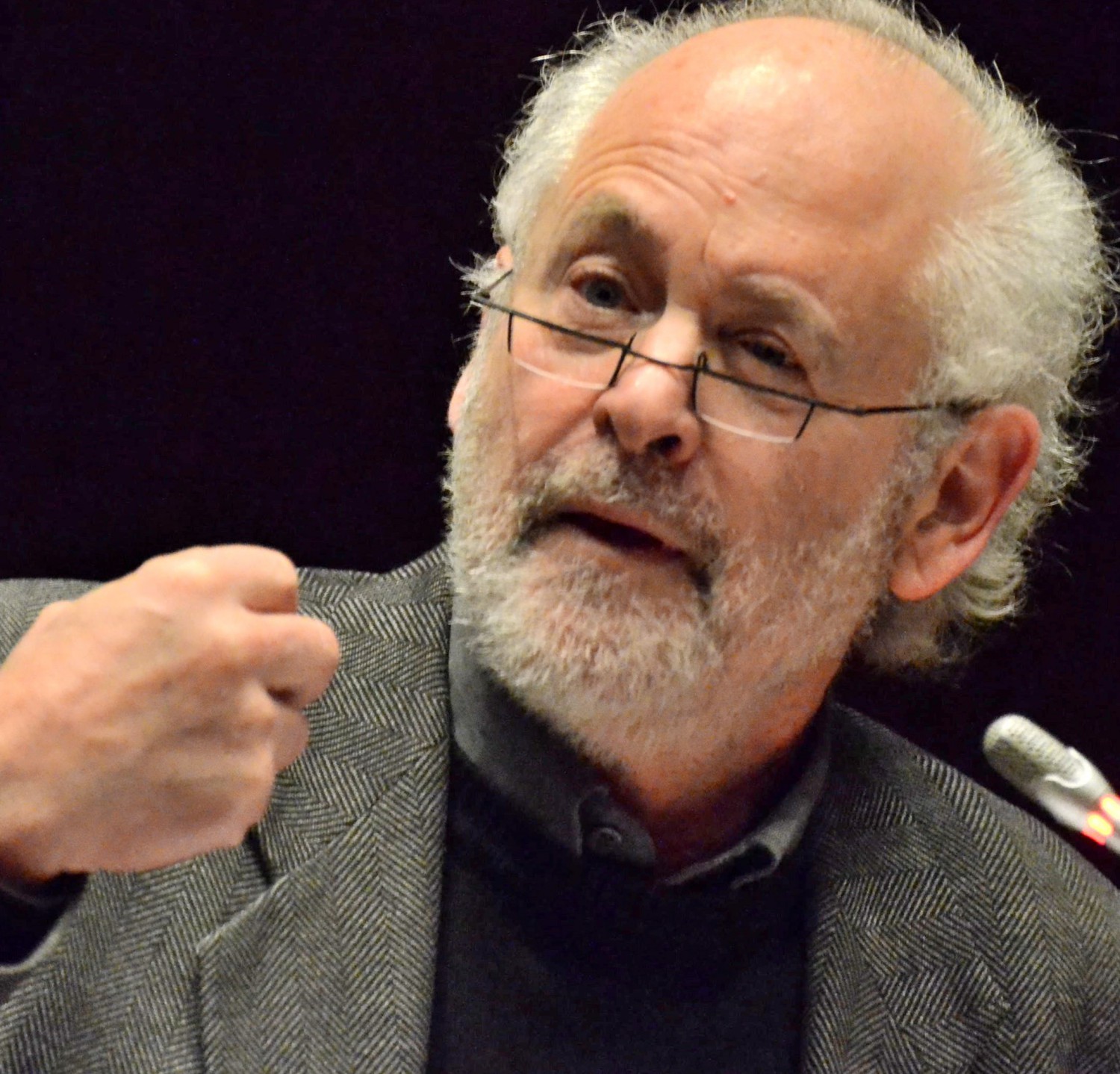

Just before the trial, I was given fresh clothes and taken for a haircut. I also decided to have my beard shaved off, since it might make me look more respectable in the eyes of a white South African judge. I also wanted to appear as dignified as possible, as I was a representative of the liberation movement.

Two things changed after I was charged and returned to Durban Central. I now had access to lawyers and could see visitors for 30 minutes, twice a week.

Although aspects of my conditions were better than I had expected, I was impatient to have my trial settled and know my sentence so I could adapt to the life that lay ahead.

It was pleasant, as well as unsettling, to be visited by friends, and for them to send me food and fruit, which was allowed prior to sentencing. This made life easier, but I kept on thinking that I should not get used to such “luxuries.”

At one point, I told people not to send special food because I had to get used to prison food. But I had a relapse after experiencing Durban prison food for a few days and rescinded the request. It was wonderful not to have to eat prison food for all three meals a day.

Although not yet a sentenced prisoner, I started to get a glimpse of what lay ahead of me. I saw the various ways in which prison rules try to rob prisoners of their individuality. There were constant invasions of privacy and attacks on the dignity of prisoners. One little thing that immediately struck me was the “Judas hole” on the door. Any passer-by could look into my cell whenever it took his fancy and sometimes other prisoners would do so, and shout obscenities at me. I felt, then, a peculiar sense of powerlessness. I could not see much of the outside from inside the cell, but anyone looking in could see as much as they liked and deprive me of any semblance of privacy. It was sometimes quite intimidating to have a person I could not see shouting threats at me from outside the cell.

From early on I noticed the prison noises, the occasional silences, broken by terrible noises, the banging of steel doors, jingling of keys, shouting and swearing of warders. No prison official speaks softly. Officers would shout at warders and warders always shouted at prisoners.

Sleep was difficult, since the young warders on patrol did not bother to be quiet. When they looked into my cell at night, they would switch on the light long enough to wake me and then go away. Sometimes a young warder would just stand around, apparently aimlessly, but lightly jingling his keys, enough to cause considerable irritation and make me realize how frayed my nerves were.

There were no direct-contact visits, and you had to speak through a glass panel. Sometimes other prisoners had visitors at the same time as I did, although they generally tried to keep us separate. I preferred it this way, because it was hard to hear above the shouting of other prisoners and their visitors.

At this time, I was preoccupied with preparing my statement from the dock. There was not a lot I could say in my defence. Purely in terms of the law, the case against me was cut-and-dried.

In a letter to my grandmother, which was dated August 18, 1975, I wrote:

“Generally I do not feel very depressed here. It is a great waste to have to spend this time locked away and conviction for a minimum of 5 years will mean that — but I cannot pity myself in this context: there are others who have far longer sentences and also went to prison around my age. Though I do not want to go to gaol, this does not mean that I have any regrets for what I have done — I would do everything, but more again. That I have done insufficient is what I regret.”

This passage is written in the tone of the revolutionaries I studied and tried to emulate. It is also a good example of my tendency to deny my own pain precisely because I knew others were experiencing worse. Nelson Mandela had been sentenced to life imprisonment. Therefore, I chose to say nothing about my own suffering.

At the time, I really did not understand what it meant to be put away for years — or know what depression really meant. I wrongly equated depression with unhappiness. I knew how to act, and how to take a defiant and unrepentant stance. But I did not foresee the real suffering that lay ahead, nor understand the toll that long imprisonment exacts. I am not sure that I fully understand it now, outside of recognising that many of my present habits are conditioned by my prison experiences.

But perhaps my behaviour was right at the time. Denying my pain was at least a strategy for coping, and perhaps an effective one. And I honestly did feel ashamed of complaining, especially when others had much heavier sentences. Complaining — as distinct from protesting — might have only wasted time, lowering my own morale and that of my comrades.

We live in different times now, and I am able to look back and be honest about how terrible it was.

The letters I wrote at the time [some of which appear in the book] , typical of my attitude of the time, now seem a little naïve. But I was forced to draw on some basic beliefs to survive those difficult times. And my convictions were, in many ways, the key to my survival.

I took a defiant stance, made no apologies for what I had done and stood with the liberation movement.